Most of us are anti-racism, and in some ways, it’s a good thing that so many people failed to see the connection between the word and the colour of the child’s skin. Offended or not offended, most of us are on the same side.

As my husband so eloquently put, “One needs education while the other deserves condemnation.” Many of us are guilty of the first, and we have a chance here to learn from it. There is a difference between unintended racial insensitivity and overt racism. It’s time for those of us who are not affected to listen to those who are. You will hear of a chilling history, and present, with the word, and why it evokes such a strong reaction.

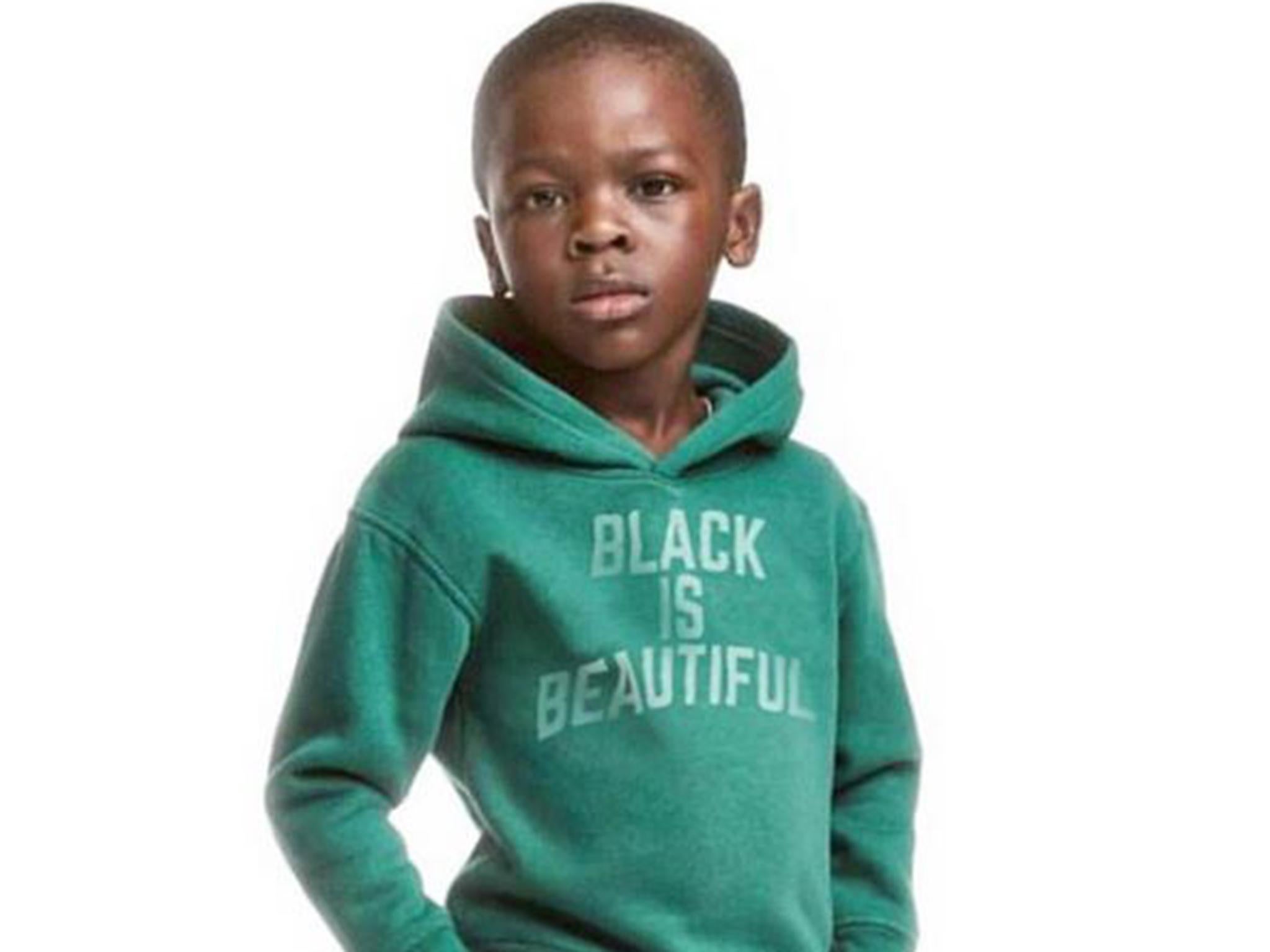

But instead of jumping on the, “Everyone is too sensitive” bandwagon, stop and ask some of the people hurt by the ad why they are offended by it. The term itself is fine, the shirt is cute, and it is okay if you weren’t offended by it. At the very least, this indicates a lack of diversity or awareness in the marketing department of their company that I hope they will address.Īnd for those of us who use monkey as a term of endearment, that’s okay. Their questionable history with race relations has cast some doubt on this, but for the sake of argument, let’s assume that the people who okayed this ad genuinely did not realize it was problematic. I would like to give H&M the benefit of the doubt that this was born of ignorance not malice. For every well-known example like above, there are countless personal stories of hurt by this slur. The equation of black people with monkeys may have happened hundreds of years ago as a way to dehumanize black people and make slavery seem more acceptable, but the hurt from it continues to this day. To see it in action for yourself, find any article on Michelle Obama, and there will be a monkey or gorilla reference in the comments. In response to a Black Lives Matter rally at the University of Northern Florida, some white freshman uploaded a Snapchat video of themselves behaving like monkeys, captioned, “What really happened at the Black Lives Matter rally. Soccer player Sulley Muntari walked off the field when his request for the referee to do something about fans spitting racial abuse at him, including calling him a monkey, were ignored. Lester commented last year that while he was giving a lecture at his school about the animalization of black bodies, across town, white male high school students were taunting a black member of their opposing basketball team with “chest pounding, arm scratching, and monkey sounds.” Last year, John Legend was taunted by a member of the paparazzi with, “If we evolved from monkeys, why is John Legend still around?” If you think that monkey as a slur is a thing of the past, you would be woefully mistaken. For many black people, seeing the word “monkey” associated with a black child elicits a visceral reaction. When you have not been on the receiving end of the word “monkey” spewed with hated. When you are not part of a group with a legacy of hundreds of years of being equated with animals. It’s easy to make these comments when you have not been dehumanized. I expect several on this article as well, but I am hoping before making these comments people will read further and gain a different perspective. I call my kid monkey, don’t you have a sense of humour? If this shirt was on a white child it wouldn’t be racist, isn’t it racist to say white kids can wear shirts black kids can’t?” This is the basic summary of the comments sections on articles addressing the shirt. All I see is a cute little boy, if you see it as racist then it’s you who is racist. “It’s just a shirt! People are so sensitive these days! Everyone is looking for something to be offended by.

Racism h and m ad full#

Indeed, the reaction of many non-black people to the controversy over the shirt has ranged from perplexed to full on eye-rolling. Neither he nor I have ever experienced the term in a negative way. The delight I find in innocently calling my child Monkey comes from a place of privilege. At five, I still affectionately call him “Monks.”īut when H&M recently ran an ad featuring a young black boy wearing a shirt printed with “Coolest monkey in the jungle” I immediately understood why it was problematic at best, and in many cases downright hurtful. He had a monkey cake, monkey décor, monkey balloons…if it had a monkey on it, I got it for him. The theme of his first birthday was monkeys. In fact, I spent the first year of his life collecting monkey themed clothing and toys for him. My second child gained the nickname “Monkey” just about immediately after birth, and it stuck.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)